“I have gone to pieces, which is a thing I have wanted to do for years.”

Jane Bowles, Two Serious Ladies (1943)

It is said that Huguette Caland left Beirut, the city in which she was born, in the year 1970 to begin a new life in Paris, leaving behind a home, husband, three children, and a lover. Of course, to say that Paris is where one goes to find existential freedom is to indulge in a n expression so trite, so atavistic, as to make one wince (nearly). And yet to veer away from it is to ignore the legion for whom Paris has been critical to their art.

But why did Caland leave in the first place? We can only speculate— the spirit is a mysterious thing— but perhaps being hemmed in by the rituals and duties associated with playing wife and mother had something to do with it. So, too, might have Beirut’s narrowly bourgeois atmosphere. “Every dress was a catastrophe,” she one told the writer Hanan al Shaykh about the social and sartorial pressures of her time. Instead of the latest fashions, Caland, the daughter of Lebanon’s first president, Bechara el-Khoury, scandalously took to wearing loose, tent-like kaftans.

There’s another clue in the interview with al-Shaykh, a writer whose own fictional characters tend to chafe at their milieu’s prohibitions. Called was marked by a pear-like girth all her life, and tells her interlocutor that, as a young person, she grew fat “as a challenge.” Who on earth grows fat as a challenge? Could Caland have delighted in shocking for shocking’s sake? The statement is as queer as it is rare. And yet it offers an important insight into an individual who seemed to be at a right angle to the world from the start— and certainly at curious odds with her good breeding. The unerring clarity of purpose!

Huguette Caland

Visage (Bribes de corps), 1979

Oil on linen

31 3/4 x 31 3/4 inches

80.6 x 80.6 centimeters

Courtesy Musée national d'art moderne, Gentre Pompidou, Paris. Gift of Galerie Janine Rubeiz, Beirut.

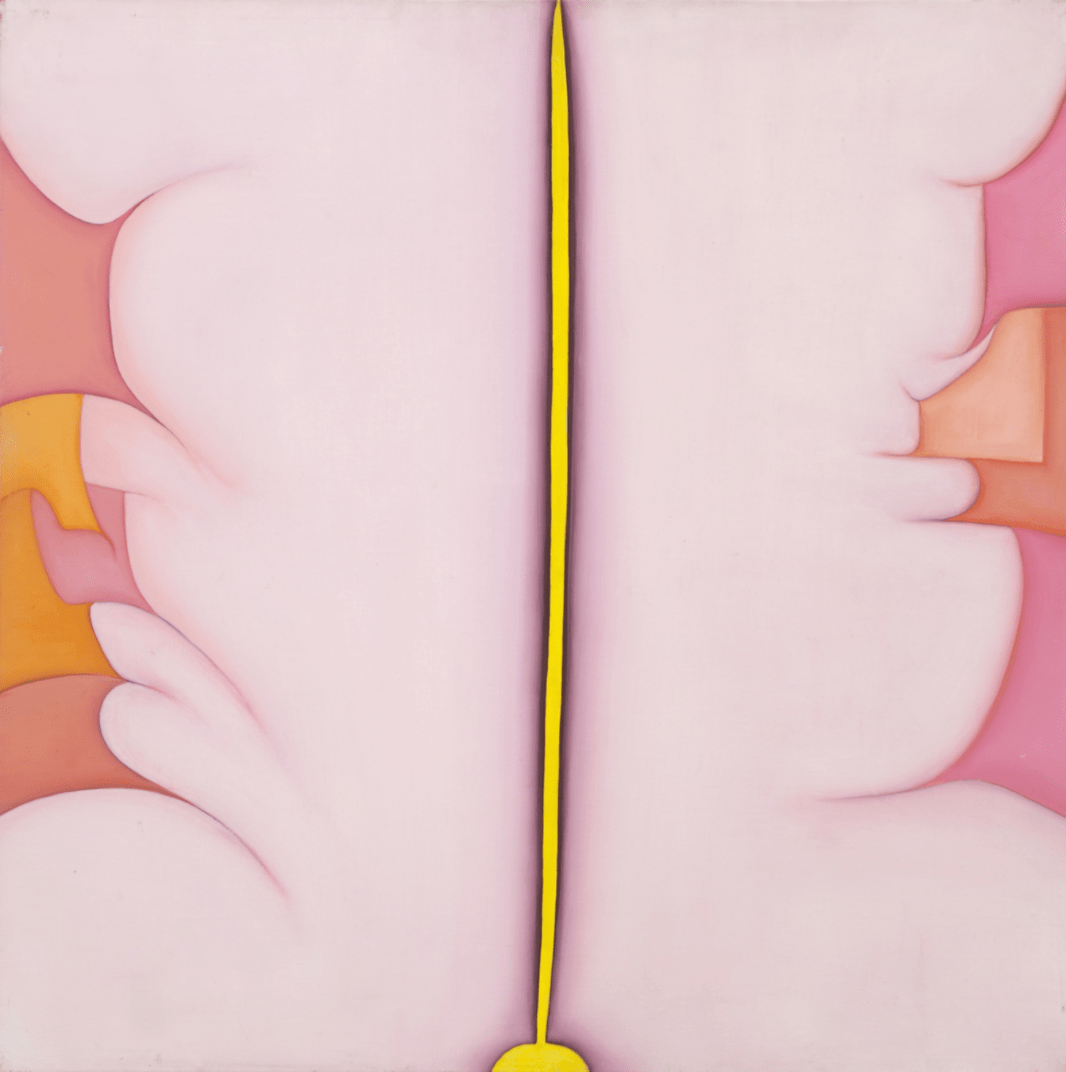

Huguette Caland

Monsieur, 1979

Oil on canvas

79 x 79 inches

200.6 x 200.6 centimeters

By the early 1970s, the body was beginning to assume pride of place in Huguette Caland’s art. An imitation of what was to come, maybe, she painted Maryam in 1969, a portrait of a woman— nude— seated casual in what appears to be a patrician living room (landscape painting: check; check; handsome vase: check). Exit, a work from the year 1970, depicts a pile-up of faces — some of them will make return appearances— smooshed into in an irregularly shaped circle, evoking the bowels of an overcrowded elevator. If nothing more, it conjures a distinct claustrophobia. An oppressive cacophony, too. In the center of it all a woman’s pubis makes a cameo. Above it, a loose breast.

In Paris, where she settled into an apartment on Rue de Berri, Caland took to making simple ink drawings that, very often, began with a simple line, doodling outwards into kaleidoscopic, acrobatic universes of their own. Their intimacy of scale, and beguiling child-like modesty, is breathtaking. And human. It was as if Caland, newly stripped of social baggage, had returned to the stuff of bare essentials. It began with a line, you might say.

Soon, she began making three-dimensional forms, including plywood mannequins on which hung extravagant kaftans (these again) of her own design. The mannequins are kooky human forms with asymmetrical, cubist hears and hokey stick legs. The surfaces of the textiles, in turn, are filled with the elaborate workings of her hand. A period designing kaftans for the fashion house of Pierre Cardin ensued. In a photo from that time, Huguette appears exquisitely tanned— ravishing— dressed in a chic charcoal kaftan of her own, blue kohl around her eyes. She’s on top of the world.

Huguette Caland

Corps bleu (Bribes de corps), 1973

Oil on linen

36 3/16 x 28 7/8 inches

92 x 73.2 centimeters

Meanwhile, Huguette’s doodly lines began to depict antic human forms. See a swell of the vulva, the curve of a breast, the sight of botoxy lips interlocked, a chaotic sea of pubic hair. Lumpy bodies lie on bodies in ecstatic tangles, dancing like charmed snakes, their flesh mingling in many cases, it’s impossible to divine where one body begins and the other ends. Orifices represent beginnings or endings or indeed both as directionally is turned on its head. These works are unequivocally sexual, and yet they are not obscene. They are also, in a sense, unwitting self-portraits.

Tas, from 1973, is a paradigmatic work from the period, a mélange of bodies. Nine faces feature; a neckline is contagious with a nose which in turn locks lips with another. Her figures’ heads are often covered in wraps or turbans. They have theatrical eyes. One can imagine them with eccentrically over-rouged cheeks, too. They are almost certainly women of a certain age, which is to say, they are not conventional sex objects. The multiplicity of heads— so many heads!— seems to call to mind the psychoanalytic subject, the divided self.

Another drawing, untitled and from the year 1972, captures bodies inscribed on bodies. A woman’s long hair is filled in with a string of almond-shaped eyeballs, evoking the scales of a snake. Out of her neck comes another face, and her breasts serve as eyes. Caland’s layering and the juxtapositions that ensue create delirious palimpsests— as if evoking hazy memories, or conjuring the multitude of persons that mark all the encounters of a life.

This should be said: Huguette Caland is funny, and a hammy humor is sprinkled throughout. Even among the most sexual and iconoclastic drawings, the sexual charge is inflected— undercut?— with playfulness. One subject’s eyes are rendered droopy and overlarge, another woman’s nose is fashioned from a penis and balls turned upside down, while a set of braids also double as a man’s balls. Limp arms hang from bodies and extend for what seem like kilometers, like rag doll appendages. Occasionally, a round mustachioed humpty dumpty male with a brush mustache apepars— a former lover, so the story goes.

By 1973, Caland had extend her drawings into color with a series of colorful abstractions she titled Bribes de corps, or “body fragments.” The rumblings of this journey could be found in an earlier work, from 1971, depicting a deep, narrow valley from which sprouts what appears to be a skinny palm tree. That work, suggestively titled Self-Portrait, summons female genitalia. In works that ensure, the lines of the body approximate landscapes— the curve of a mountain top or the bend in a river or even the occasional lonely markings on a map of a vast desert expanse. One painting, for example, evokes two lumpy piano legs ending at knobby knees, or alternatively, two hills under an azure sky. Another features a lonely flesh-colored breast. And yet another captures two body surface gently making contact. Oh, and crasks of the ass abound.

Caland’s pronto-bodies are far less busy than Georgia O’Keeffe’s mille-feuille genitalia. Instead, they’re closer to Ellsworth Kelly’s organic forms distilled from everyday life, or, even Edward Weston’s closely cropped photographic nudes. Like Weston, Caland could transform a corner of a thigh into an entire universe. At moments, these works also recall the abstraction of her Lebanese contemporaries Saliba Douaihy and Etel Adnan.

A lover’s influence is palpable, too. George Apostu was a Romanian-born artist whose roly-poly sculptures took their inspiration from the worlds of folk are and the ethnographic. His drawings depicted large, curvy, nubile women. Apostu and Caland had met around the year 1983 in Paris, where he settled after leaving his native Romania. Her work that time reveals drawings of the two of them in sundry sexual positions. All the encounters of a life.

I never sit down in front of a drawing or a painting and think, "I'm going to paint something erotic." Erotic means life, there is no life without some form of eroticism. You can't separate eroticism from life.

- Huguette Caland

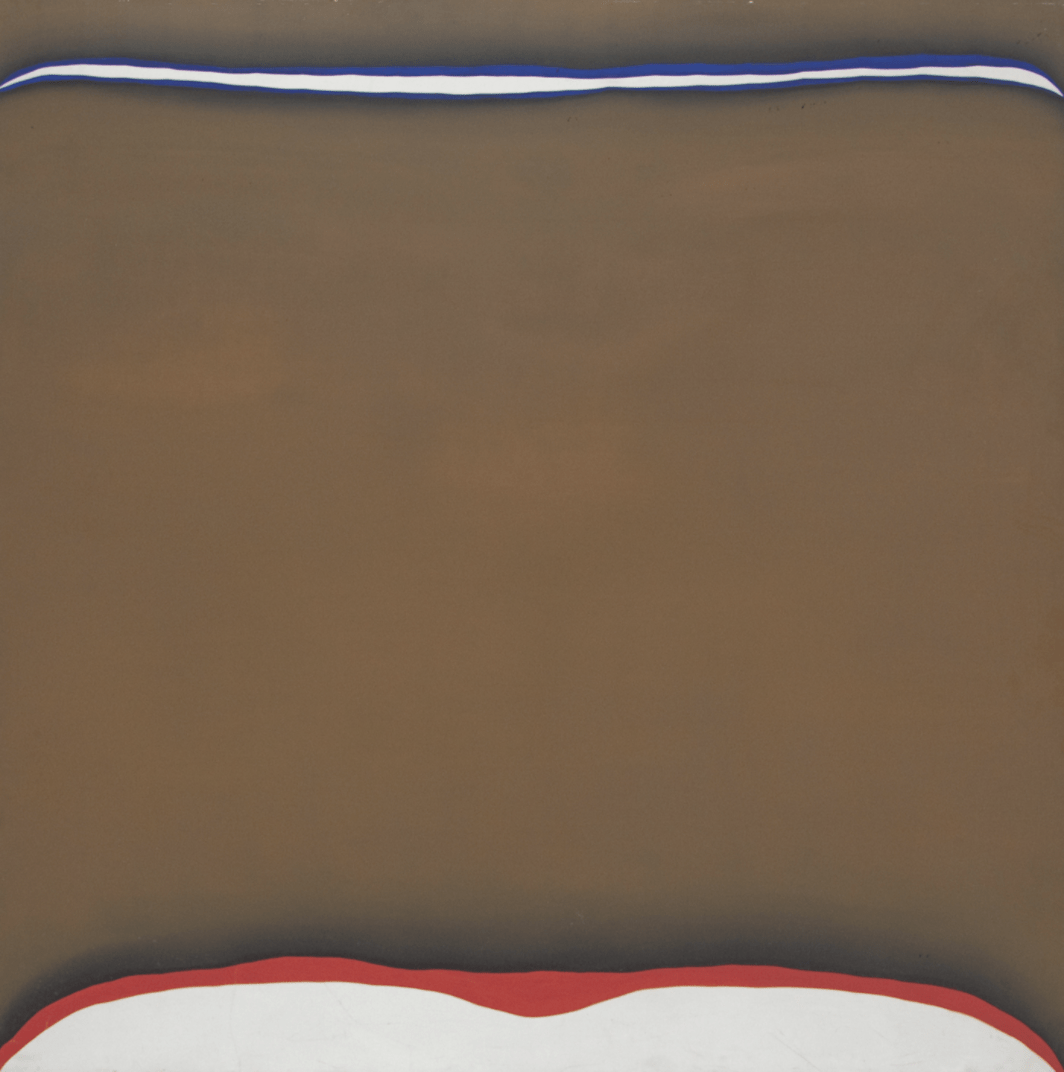

Huguette Caland

Bribes de corps, 1973

Oil on canvas

59 1/8 x 59 inches

150.5 x 150 centimeters

There’s a story that the American artist Hannah Wilke used to tell. It went something like this: When Vito Acconci masturbated under a wooden platform, it was called “Conceptual Art.” When Wilke herself set out to make a piece involving herself getting massaged in a massage parlor, her gallerist said this: “Hannah, why don’t you come up to my hotel instead?”

Well-known double standards aside, Huguette Caland would not be the first woman to make high art from her sexual exploits. There’s Joan Semmel, who painted lusty bodies entwined. Or Cosey Fanni Tutti, who worked as a model in pornographic films and magazines, which in turn became the raw material for her art. More recently, Sophie Calle, has made art out of her jilted— and jilting— lovers. Frances Stark, for her part, has created films— and literature— out of online trysts with anonymous inamoratos. Examples abound. And yet I’ve seen no other “erotic” art quite like Caland’s.

In The Dangerous Sex (1964), H. R. Hayes chronicled perceptions over time of women as unclean Pandoras with evil boxes, agents of the devil that pose threats to male supremacy. Caland’s treatment of female sexuality— cozy, quirkily sensual— is as far from “evil” as can be. Her women having sex evoke fun and freedom. Theirs is a mirthful sex without shame, without inhibition. It is no wonder that, years later, a studio assistant recalled that Caland had had a sticker on her computer which read “Boobies.” [Cut to laugh track]

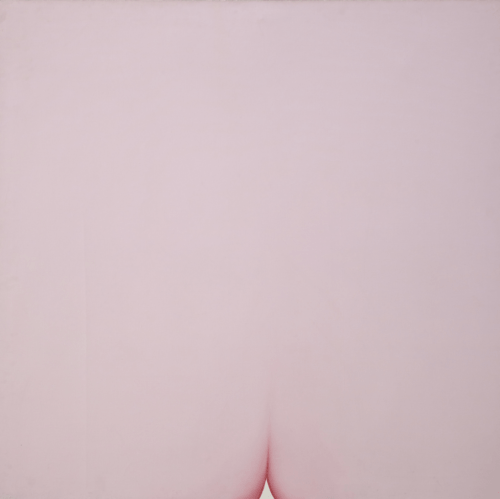

Huguette Caland

Self-Portrait, 1973

Oil on linen

47 x 47 inches

119.4 x 119.4 centimeters

Private collection

But are Caland’s works actually erotic? Undoubtedly. And yet they demystify eroticism by embracing a remarkably diverse array of bodies— without pretentiousness, without artifice. These are imperfect bodies caught in perfect bliss. Her daughter Brigitte had said that if asked, Caland would argue that her own body had server her well over the years. “She wasn’t uncomfortable with her body,” she notes. “It was always other people who were uncomfortable with it.”

Given her lightness of touch, Caland has other spiritual relatives among artistic peers. Like the voluptuous and eccentrically colored nana of Niki de Saint Phalle, her forms seem to express and unabashed delight in their carnal liberation. (O’Keeffe’s vaginal landscapes, made decades before, never had such a sense of humor.) In their occasional cartoonishness, they are also not wholly unlike Dorothy Iannone’s stylized nipples, penises, and furry pubis too (though they are certainly less overtly political).

Motley comparisons aside, what, one might wonder, does Caland’s work have to say about women, or Lebanon, or Arab women, or women who abandon their husbands anyway? It turns out: not all that much. Her “bribes de corps,” for example, are fragmentary— partial— incomplete; they aren’t at all stand-ins for larger narraties. If Caland’s zigzag work and life have taught us anything, it is that it is sui generis; her choreography is her own.

One final story. At the turn of last century, Huguette received a delegation of Arab women at her Venice studio, years after she had left Paris for California. (“Caland sounds like ‘California-land,’” she was known to say. She moved not long after Apostu’s passing.) Above her dinner table hung drawings of her former lover, nude, his penis alternately flaccid and erect. Did she think of removing the paintings, her daughter asked, in advance of the visit? Not for one second.

Apparently, the meeting went very well.

In this way, Caland’s journey reminds me of the heroic literary duo of Mrs. Copperfield and Ms. Goering, two bourgeois women of fine bearing who deliberately jettison their square, respectable lives to find fulfillment in the exotic and lowbrow in Jane Bowles’s cultish novel Two Serious Ladies. By the end of the tale, which was published in 1943 and met with almost universally baffled response, Bowles’s two ladies sit in a louche bar looking back at their lives. Mrs. Copperfield, turning to her friend, says: “I have gone to pieces, which is a thing I have wanted to do for years… but I have my happiness, which I guard like a wolf, and I have authority now and a certain amount of daring which, if you remember correctly, I never had before.”